Why Your Product Should Have An Ego

Why Your Product Should Have An Ego

In this weekly series, I opine on how language and content affect the way we understand the products and services around us. I do this for your entertainment and education (and, of course, to remind you that if you’re looking for a freelance copy, content, product, or technical writer… yada yada, hire me).

Amidst the chaos of Trump’s presidency, the increasing demonization of tech CEOs, and the advent of #metoo, the biggest egos of our time have been universally renounced.

As a result, the collective “we” has become transfixed on the common bond that binds all of our modern day ne’erdowells: their egos.

Yet, as Psych 101 and spirituality writers tell us, “ego” isn’t necessarily a bad thing. On the contrary, when used correctly, a bit of ego can beget significant results.

This is particularly true when it comes to putting a product into the world, and there’s at least one famous example that proves how infusing our products with a bit of ego can have a huge impact.

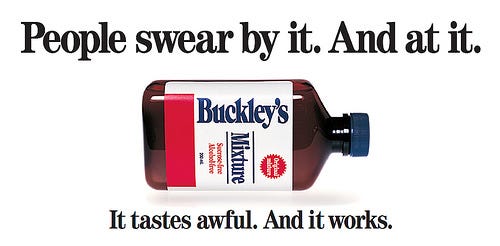

That example? It’s awful. And it works.

Wait, What Are We Talking About?

Even the strongest Canadians among us will likely wind up coughing dry heaves of air this winter. And when we do, we turn to our local pharmacy to buy one of the worst-tasting salves the health aid market has ever produced.

We buy Buckley’s.

Originally invented in 1919 by Toronto pharmacist William Knapp Buckley, the mixed collection of mostly-natural ingredients offers to consumers none of the sweetness or smoothness of other brands but at least equal efficacy.

So what makes Buckley’s so remarkable?

From the moment he invented his foul-flavoured brew, Buckley infused the product with an ego—a strong sense of self-awareness and self-esteem. And that’s been evident from the very moment that product was first announced to the world through to its major market position of today.

What Happened

With such a strong sense of self identity, the product’s go-to-market strategy was quite clear: Buckley simply had to let the product be unabashedly proud (and loud) about what it was.

From day one, the message to the market was profound and arrogant and outright astonishing.

In bold print on the Classifieds section of the Toronto Star, Buckley headlined his product with but two words: “SAVING LIVES”.

With the market’s attention caught, his announcement continued with the kind of bravado that we might imagine the most egotistic speaker trumpeting:

That’s what Buckley’s White Bronchitis Mixture is doing every day. It is curing Bronchitis, Coughs, Colds, Bronchial Asthma, Hoarseness, when all other remedies failed. I sell it under an iron bound money back guarantee to cure any of the above ailments. No cure no pay. Can I do more than this to prove to you its wonderful healing power? Ten times more powerful than any known cough cure, acts like magic, one dose gives instant relief. Never wait for a cough or cold to wear off. It wears away the lungs instead. There is none just as good.

Over the years, his son Frank Buckley and their team would continue to work and refine that message, until the company’s current, timelessly, proud, and resonantly self-aware proclamation was made:

It tastes awful. And it works.

And what a proclamation it was.

The Result

The story of Buckley’s success is well known. In an industry where new disruptors were as rare in 1919 as they are today, the company’s ego-infused vision, product, and marketing led it to resounding success in its early days.

Even after falling into a slump during the 70s, the company’s “Bad Taste” campaign rekindled that sense of ego and resulted in a marketshare increase of 10% in Canada and catapulted the brand into the global marketplace with similar and massive success in the Caribbean, Australia, New Zealand, and the U.S..

By 1992, Buckley’s became the number 1 cough syrup in Canada, and by the 2000s, annual sales topped $15 million.

The Takeaway

In spite of the brand’s messaging clarity and unique positioning, there exists no truth to the company’s claims. Buckley’s is not any more effective than a spoonful of honey, let alone any other brand’s product.

The company’s claims were, from day one, as they are today: unsubstantiated and ego-driven.

But that ego continues to provide the company with a clarifying rallying point for its product and marketing efforts, and to to this day, the company’s product development remains resolutely focused on delivering against ego-centric proclamation.

Perhaps no one boils down the lesson to learn here better than Buckley’s itself:

In our complex and constantly changing world, consumers are looking for demystification and simple effectiveness in the things they buy, and the Buckley’s® product line offers just that.

The beauty of Buckley’s use of ego here is in its ability to articulate that very clear, crisp takeaway with a confidence that inspires action in its consumers and creators alike.

TL;DR

Ego may be a bad thing for presidents and politicians, but it can do wonders for your product.

Give your product a little ego and let it boast about being really good at something: doing so will let you more crisply articulate its promise to the market while helping you focus on delivering that promise in parallel.

What about you? Any lessons you’ve drawn from this? Respond away. And if you’d like to learn more about me or my business, visit www.frankcaron.com.