The Rise Of The GM And The Case For Variably-Comped Product Managers

The Rise Of The GM And The Case For Variably-Comped Product Managers

In these periodical posts, I opine on prose, products, and profits. I do this for your entertainment and education (and, of course, to shamelessly promote myself and my team, as that’s what you do these days.)

Here’s a surprisingly and seemingly difficult question to answer, particularly in Toronto: who ultimately owns “product P&L” in a start-up?

Is it the COO? Is it the CFO? How about the CPO or the VP of Engineering? Or does it simply default to the CEO?

In my experience (at least as far as Toronto is concerned), most start-ups do a horrible job at assigning and empowering a single point of accountability for product P&L—and their products suffer for it.

Recently, as the city’s start-ups have become scale-ups and established companies (and begin finally taking cues from successful companies outside of our shoulder-chipped echo chamber), the General Manager role is emerging as one answer to that question, particularly as prominent international companies have created Toronto outposts (e.g., we need one right now for Lime so I can get my electric scooter on).

But before a General Manager (or COO-in-waiting) makes sense, who should actually own product P&L?

As you might expect, I have opinions — hastily drawn, poorly thought through, and likely deeply flawed opinions, but opinions that I feel compelled to assert thanks to my need for constant external validation and attention.

(I am a millennial yuppie, after all.)

What is “Product P&L”?

Before I get into my views and create a shit storm of rebuttals, I first want to explain my perspective on profit and loss in a product company.

The rise of once-start-ups like Amazon and Facebook may have trained a cohort of entrepreneurs to believe that profit is irrelevant until you hit scale, but for the rest of us (read: those that value businesses which generate more value than they consume), profitability is incredibly important.

The key to building a sustainable business is to invest capital back into the business effectively to stimulate growth; doing so with profit rather than equity (read: VC Scrooge McDuck money-bags) allows the business’ original founders and ESOP’d employees to benefit more substantially for their effort and lost youth.

Built atop that core foundational business tenet is one of my most tightly-held beliefs about building great products: just as a good business manages itself against its holistic P&L, so too should a good product of its own P&L.

So how does one actually calculate a product’s P&L? Here are the two formulas I use:

Top-line Profitability = (Monthly Product Revenue) less (Avg Monthly PD Salary times PD Staff Count)

Unit Profitability = (Avg Customer LTV) less (Avg Monthly PD* Salary)

*PD = Product, Dev, and Design resources

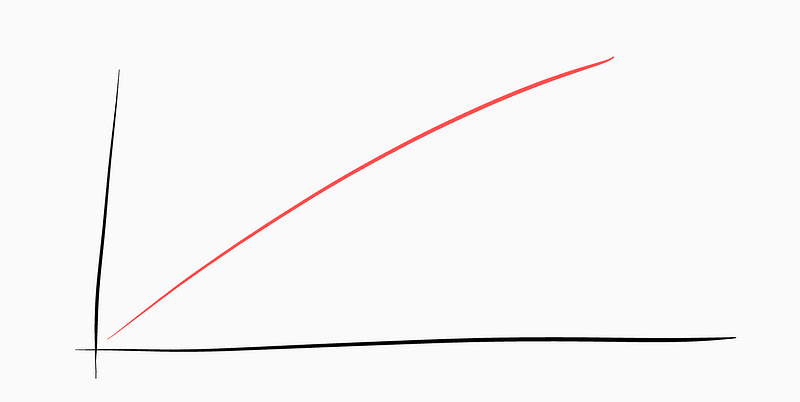

Success on the top-line during the start-up phase is pretty simple: work as fast as possible to get to a greater product-driven revenue than the burn on dev investment into obtaining that product-driven revenue. This is in many ways very similar to the common metric of “revenue per employee”.

As stated, though, this is necessarily product-specific measure and is also necessarily imperfect. Product revenue will be driven by more than just the product, obviously: both sales and marketing will significantly contribute to that number.

That’s why the usage of that top-line metric should be about multiples as soon as break-even is achieved.

After product-market fit is found and the start-up becomes a scale-up, product revenue affected by sales and marketing will be more often than not incremental rather than exponential. It is product development’s job to find the exponential gains and affect product profitability in multiples.

The same is true for the unit profitability. Adding more valuable customers by having sales sell longer commitments will multiply unit product profitability, but that has its limits and eventually only product development can affect unit profitability in multiples.

The Case For Variable Product Manager Comp

So, with that lens of profitability, we come back to the question we started with: who owns product P&L?

The right answer should be the product manager. A VP will own the product P&L of the full portfolio, a Director will own product P&L of a given segment or logically-seperated part of the portfolio, and an individual PM will own product P&L of a given product or part of a product.

A good product manager, in my opinion, is one who can steward a product towards greater product profitability.

Here’s the problem with that belief, though: taking that absolute accountability stance necessitates giving absolute control. No one will agree to own a metric as sensitive as profitability unless they can be empowered to make decisions, plan the strategy, and execute.

And therein lies the rub, at least based on my experience in Toronto: product managers are rarely given control and more rarely own product P&L.

For the most part, a good product manager in Toronto is one who can work well with dev, talk to sales, schmooze with execs, and ship on time. Nothing more. And somehow, that warrants $120,000+ a year or more in salary.

Fuck that shit.

I know I can’t look myself in the mirror and be okay with that as an individual contributor PM, and I sure as shit expect way more of my team. That’s why I’ve been trying to figure out how to fundamentally change the way that we run, and comp, Product teams.

Proposed Comp Structure

Rather than taking smart people, giving them a huge salary, and sticking them in a chair to take orders from stakeholders, I have been mulling a move towards a model wherein a Product Manager is incented to more immediately (and necessarily) share in the profit but is required to more actively and literally “manage” the product as a business.

Critical to this plan, though, is the complimentary “give” to that take: we need to empower PMs to have the autonomy (read: exec buy in) to steward the product towards profitability based on their “boots-on-the-ground” view of the battlefield.

Ergo, I believe PMs should be compensated something like this:

- Base salary = today’s base * 0.75

- Quarterly bonus = (today’s base * multiple based on lift to product profitability) / 4

As an example, say my direct report PM is making $100k annually today and we’re doing $50k in MRR.

We decide, for simplicity’s sake, that the multiple will be 10X the percentage increase.

Beginning in Q3, her salary is dropped to $75k, and during Q3, she is able to ship a feature which positively affect profitability by 5%. At the end of the quarter, she is awarded a bonus of $12,500 ($100k * 0.5 / 4).

Assuming MRR stays flat, the incremental benefit of her work has saved us $2,500 in operating cost for that quarter. That means her bonus has a payback period of just 5 months, even though the value of her work will begin to generate ongoing net profit 5 months from now. Those are good economics.

Thanks to her efforts, this PM earned effectively the same salary as she did before the change, but she was able to completely deprioritize and more easily ship product given her new focus on a single top-line metric that everyone cares about: product profitability.

What This Solves

I see a few major advantages to this approach:

- Sales, Marketing, and Product are immediately more aligned, as their success is measured on money coming into the business

- Exec is made more comfortable ceding control of direction to PMs because their impact can be clearly quantified

- The business benefits from having a single point of accountability for driving product profitability

Where This Fails

Ironically, most PMs would probably hate this.

The majority would be immediately paid a ton less and would suddenly be so much more concretely measured and pressured. Many would wash out (myself included, most likely), as increasing product profitability is really hard and only gets harder over time.

Many of today’s tech companies would be unable to accommodate such a model, too. The Product Manager would need to have significantly more control over (or rather alignment with) Dev, as any misalignment between the two parties would set the PM up to fail.

(N.B., A real-world analog here would be Sales Managers whose comp is a function of their team members’ performance and comp.)

A lot of execs would likely reject the model, too. Giving any one employee who isn’t heavily vested complete control is risky in even the most ego-free start-up environments, let alone those wherein the senior leadership need to feel the heroes and #mansplain how business is done to all subordinates in sight.

To be fair, a few companies in Toronto use bonus programs and quarterly goals to attempt to achieve similar results, though I’ve yet to see this effectively implemented for product managers in my experience as an individual contributor PM.

The Takeaway

Admittedly, as I’ve worked through the process of learning how to manage product managers, I’ve struggled to create the environment for my team that I feel I’ve been deprived as I grew up a PM. I suppose that’s very paternal.

One of the reasons I’ve grown so fatigued of the PM role in my own career as I’ve aged is that the role, generally, meanders between the business and the build-out in a manner that often necessitates the relegation of the role’s actor to a position subordinate to the loudest voice in the org — perhaps a heavy-handed “product” CEO who isn’t ready to let go, or a domineering sales team more concerned about this quarter than the next, or even (as a best-worse-case) a vocal minority of old customers who the business is too scared to evolve beyond.

Transforming the comp model, and indeed the focus of the role, toward something more concrete and directly tied to a business metric that can be objectively measured and managed, feels like the salve for my team to the pains I’ve suffered before them. It feels like the trojan horse to create a world in which PMs aren’t just project managers or “tech translators” or “idea” people. It’s not perfect, admittedly, but it’s a move from current state to better state.

Alas, I fear the only product managers who would want such a comp model and such autonomy and such responsibility are those that will simply become entrepreneurs themselves, where they’ll own product profitability by necessity rather than design.

There must be a better way. The hunt continues.

What do you think about product profitability? How would you, as PM, like to be measured and managed? Have you seen something amazing that we should learn from? I want to hear your thoughts. Comment here, or reach me at http://www.frankcaron.com.