The Ballad Of Product Manager #1

The Ballad Of Product Manager #1

If I’ve learned anything in my career thus far, it’s that there is no worse feeling than feeling less valuable as time goes on.

Yet, that is the ballad oft sung by many early stage employees and one sung, in my experience, most painfully by Product Manager #1.

(And yes, I fully appreciate the irony given my past proclamations.)

The Story So Far

I have been fortunate to spend the better part of my career in the fine art known as product management.

Even from before I knew the role by name, I worked as a creative designer getting customer feedback to improve the product at a game company; as a business analyst gathering requirements at a gambling company; and as a technical writer communicating and marketing releases at a few different enterprise software companies.

I was also fortunate enough to spend a great deal of time in different start-ups, all of which I’ve watched grow and a select few of I’ve watched become very successful.

That said, after 10 years, no experience has been more personally painful than my experience I’ve had at my current company.

Touch And Go

Names unnamed, my current company has already proven to be successful and will continue to be so thanks to the hard work of the team I work with.

Sadly, that team is the team that was brought in to replace me.

I joined as the organization’s first product marketer. After spending years working as a product manager and technical writer prior, I wanted to expand my skill set and my penchant-meets-passion for communication to help the company better educate its sales force and attract prospects with accurate, timely, and compelling product story-telling.

Alas, it wasn’t long after arriving that I found there wasn’t yet a product team to work with and shortly thereafter that I found myself as Product Manager #1.

What followed was months of learning the customer with our intrepid Customer Success and Support teams, defining and refining the development process with our eager Engineering team, understanding the prospect with our restaurant-savvy Sales team, and internalizing the market with our creative Marketing team.

After months of hard work and 22 hour days, I had helped to build a foundation for the company’s future product development. We had a roadmap. We had a schedule. We had training and enablement and foresight and strategy. We had data. We had way more than we used to.

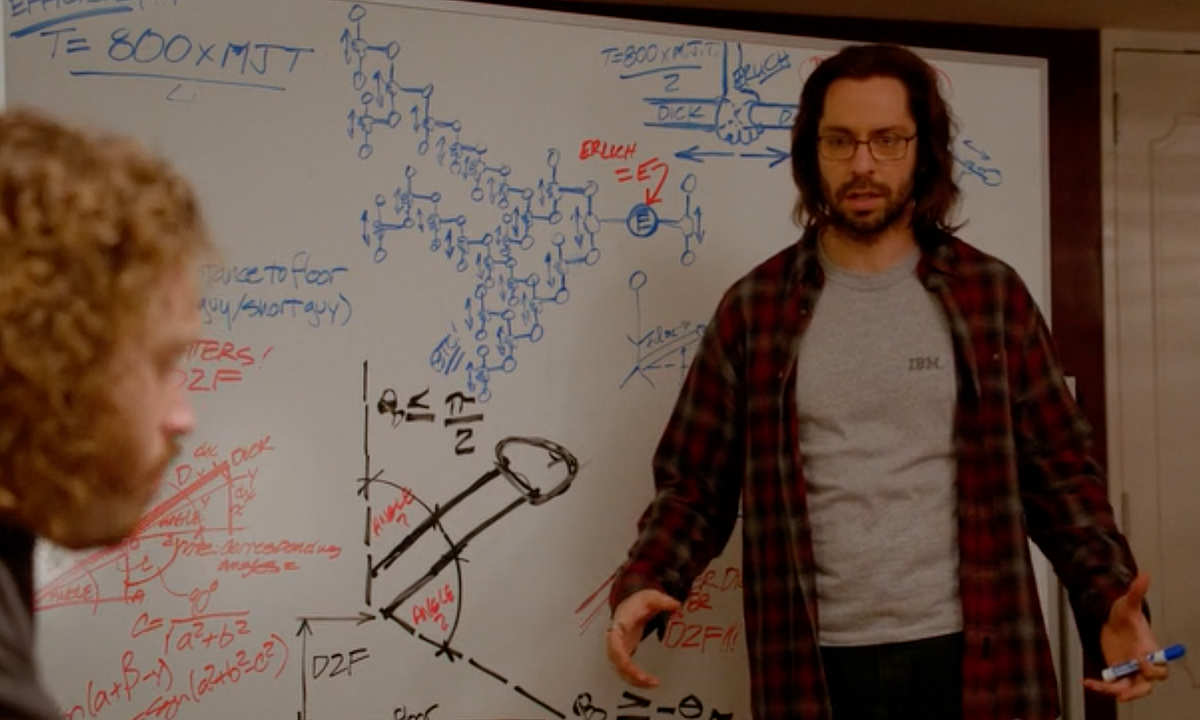

But we still only had me. I was stretched thin to the brink of snapping, constantly wearing beaded sweat on brow with clumsy short-term roadmap in one hand and in the other clumsier-still designs—the kind that the CEO could only help but pin on his fridge like they were the “nice try, Junior” crayon drawings of his infant child.

Thankfully, he had mercy on me. He found a VP of Product who had done it many times before, and she came to my aid with her ample experience and her vast network.

BOGO-FOMO

Her first order of business was to replace me.

Slowly, my one role became two. Then four. Then seven. A dedicated UX team. A dedicated associate product manager with direct experience as a past customer. A dedicated technical product manager. A dedicated QA manager.

Suddenly, I was no longer the hero. Suddenly, I was no longer the center of the world. Suddenly, I was no longer who people came to for answers; I was no longer smarter, better, more informed; I was no longer the visionary, the savant, the savior.

I was becoming what I feared being most: I was becoming useless, and the pain therein was unbearable.

I became defensive.

You guys don’t have context! You’re going to fall into this trap!

I became closed-minded.

I don’t think that’s going to work. I failed at pulling that off before.

I became detached.

All I can offer is my opinion. Take it for what it’s worth.

The world had evolved beyond me, and in my desperate need to feel useful, I couldn’t see that I was in fact hurting the team.

I turned in on myself and was hurt by any success of my teammates. I drew out of team conversations. I willfully ignored social invitations. I turned up my nose at new perspectives and scoffed at new recommendations. I went around my team to push my own agendas with my own ideas.

They couldn’t understand the context already! I’ve been doing this for more than a year! They don’t even know anything yet! They just got here!

And after days of what felt like depression, after weeks of longing to add value and flailing around in pursuit of being useful, I realized the truth.

I was slowing the team down.

The Multiplier Effect

It was only when I hit this rock bottom of sorts that things changed.

When I realized that I could offer pointed, well-informed insights into managing the process and understanding the customer, I realized I had more value to offer than ever.

I totally changed my focus and I was renewed. I began to listen and observe and when prompted began providing business insights, specific customer use cases, and context to the team at large based on my experience.

I gave specific examples where I could, and I introduced contacts and customers that could do that for me where I couldn’t. I resisted the urge to dictate and instead directed. I helped the team to discover rather than to be discouraged.

My irrational fear of ceding control began to subside, and I was free to focus on bigger strategic initiatives that only I could contribute to.

It all seems so clear now, in retrospect.

A team of one cannot scale a business, and Product Manager #1 is just that: the first player in a much bigger team.

Being close-fisted with the vision and being unwilling to help distill knowledge and accelerate the learning of the new hires was not helping the company.

As my behaviour shifted, so too did the results. I wasn’t slowing down my team or the process at all: I was in fact speeding it up. In less time, the team was able to poll customers, test designs, build features, and deliver reliable product.

I’d became a multiplier for the team — I became more useful, not less. I no longer needed to be Product Manager #1, because I was a player on a team that was capable of far more than I was alone.

Happily Ever After

Perhaps these lessons are unique to me—and perhaps not. In either case, I took away the following for my future adventures:

- Product Manager #1 is just that: the first PM on an eventual team, so act like it and plan for it. Understanding that from day one will accelerate your ability to build better products faster.

- Use your head-start to gather and document both customer-based evidence and specific use cases. Your eventual team will eventually thank you if you can provide documentation in the form of customer feedback, recorded interviews, or organized feature requests that support your opinions and experience.

- Remember that your larger goal as the team scales is to accelerate the learning of your team. Making their decisions, and doing their research, for them will not allow them to internalize the customer needs any faster nor help them to learn for themselves in the future.

Now, about that whole product marketing transition thing…